Background

In the 1930s, the American focus on behaviourism turned the linguistics world from the science of signs (semiotics) to one aligned with one of the great scientists in history, Pāṇini, who lived perhaps as far back as the 7th century BC. The use of Pāṇini’s linguistic model by Leonard Bloomfield led to linguistics excluding meaning, such as in the influential Chomsky monograph, Syntactic Structures, published in 1957.

My proposed move back to semiotics is a side effect of the highly influential work of Robert D. Van Valin, Jr., whose development of Role and Reference Grammar (RRG) over the past 40+ years creates a clear distinction between the words and phrases in a language (morpho-syntax) and their meaning in context (contextual meaning). RRG views the world’s diverse languages with a layered model that links from morphosyntax to meaning and back using a single algorithm.

For AI to emulate humans, it needs far more capability than today, such as with a simple hierarchical model: a basic animal brain capability — and it needs meaning!

The Use of Meaning Starts Next Generation AI

In 1956, visionaries including John McCarthy and Marvin Minsky started to focus on how to emulate what humans do. They called their new field “artificial intelligence.” Today, we call it AI. But the search for machines that emulate what humans call intelligence continues with disappointing results.

There has been no sign of Rosie the Robot, the robotic maid and housekeeper from the Jetsons. Nor has there been a sign of Hal from 2001: A Space Odyssey. Hal was a little bad-mannered, so perhaps that’s OK.

What went wrong?

Time passes quickly, but science progresses one funeral at a time. That’s the concept created by Max Planck, and he’d know!

We will create real AI, but first we need to clear the decks of the old ideas and bring in the scientific method.

Today’s article considers my blueprint for the Next Generation of AI – something that those visionaries from 1956 would cheer about, even though it means some of their expertise and assumptions about computers would be excluded.

Computing is the wrong model

You can’t think about today’s limitations in AI without seeing the parallels with the digital computer’s weaknesses. Data in a computer is often emulated on a piece of paper. Draw some boxes for the data’s elements and then write numbers or characters in the boxes. The numbers or characters are one of the many forms of binary encoding performed in today’s computers. Next, if we want to work with the boxes, we use information theory to accurately copy the contents elsewhere.

For a brain, this is an alien concept. Brains are relatively slow machines in which their elements, neurons, activate in a few milliseconds. That leads to the 100-step rule, a perplexing suggestion that our reaction time to complex events only allows for 100 sequential activations of neurons.

Imagine writing a program in which you need to recognize a complex scene with visual, auditory and other sensory elements and, using some kind of reasoning or program, decide to take an action, and then initiate the necessary motion with a large number of muscle activations. This program cannot exceed 100 sequential steps!

The current craze for parallel processing is an alternative approach using Graphical Processing Units (GPUs), but computers start with at least millions of times faster speeds than our brain, and that model’s results still falls short of human capabilities.

Parallel processing embraces the 100-step rule, but how does a brain implement it?

Patom theory is a model of brain function I promoted in the early 2000s to deal with what we know a brain does.

Unlike a computer, a brain starts with a large number of sensory inputs. In the eyes, millions of signals indicate the light and colors received. In our ears, signals indicate the range of frequencies of sounds received and also the position of our head in relation to gravity for balance. We have a lot of sensors that help us understand the world and our position in it!

Rather than storing data to hold information to send around, a brain appears to store information only where it is first matched and, using a hierarchical system, patterns combine bidirectionally. In theory, we could recognize a room full of people from visual inputs to our eyes by direct analysis, but that’s a lot of processing! Where would our brain start to find the people in the room’s image?

The principle in Patom theory to meet the 100-step rule is to match patterns at the edge where sensors connect and then combine them uniquely. Unique forms eliminate the need for search because only one copy of anything is stored. Large patterns are refined into decomposed combinations as discovered, supporting ever smaller sets of patterns still combining into the original ones.

As patterns are composed across regions, the bidirectional links assemble the linked-sets concept. Full patterns are assembled as a collection of earlier patterns stored in the senses – using the reverse links. Linked-sets or just linksets physically connect atomic patterns. Brain damage effects are therefore subtly different between the loss of the connecting links (white matter) and the pattern storage (grey matter). Regions are the central element in Patom theory, not individual neurons, typically with many regions in a link-set to provide a level of redundancy.

Patterns are sequences and sets. Motor control illustrates this model as large numbers of muscles are activated and simultaneously deactivated in a sequence to facilitate an animal’s smooth motion.

These patterns are bidirectional as seen in the anatomy of brain regions. This means the initial patterns are learned and stored bottom-up with edge patterns combining to form multisensory patterns. The bidirectional nature makes these patterns also top-down, enabling pattern fragments to match what is expected as well as what is seen. A leopard’s tail, for example, matches with the full pattern of a leopard if recognized, giving the visual system a valuable survival benefit.

Brain regions in this model are all alike. Patterns from any sense are recognized in regions. Similarly, this model is proposed to function equally for muscle controls as motion requires the coordination of large numbers of muscles in sequences along with sensory inputs, including balance, proprioception and other features that support effectiveness.

In summary, a brain can store complex patterns in theory with Patom theory, while the concept of creating existing computational models based on encoding has been ineffective. Worse, encoding doesn’t appear to align with brain function. There is no obvious encoding of information in a brain. Patom theory provides a plausible alternative.

What is Meaning?

In a brain, meaning is the recognition of the set of possible, known combinations with any pattern. Earlier animals in evolution use the meaning of a situation to select flight from predators and the chase of prey. Such actions are complex combinations of senses and motor control.

In humans, the science of signs, semiotics, enables improvements over this basic use of meaning in earlier animals.

Knowledge versus Meaning

Meaning is the building block of brains as described, but knowledge is best defined with a distinction to meaning. The storage of meaning across the brain involves all concurrent elements, in context, but its building blocks are not always constrained.

The idea of a fact expands on this further.

Cognitive dissonance stops us from recognizing more than one contradictory thing at a time. Optical illusions illustrate this. But in the real world we can retain multiple, contradictory ideas. Computer scientists try to limit responses to stated facts, but that’s not how our brains work. We can know, in context, that some people believe X and others believe not X.

There are no Facts

In a brain contradictory ideas cannot be held at once, compelling a choice between them. But equally, the concept of a fact isn’t aligned with brains, because brains operate at the level of the full pattern, not just the subsets.

For example, one element of an episode in the Wall Street Journal, say, can include the meaning: “Trump is a genius.” Another in the New York Times can contain the contradictory meaning: “Trump is a moron.”

Personal opinion can be one of these items, both, or neither, because each element is simply the meaning of an event or perhaps, named more effectively, knowledge.

Align Computer Science Knowledge

Linguistics like Role and Reference Grammar model the meaning of sentences. As a model of human language, RRG models can be as lossless as a human can recall. In order to manipulate these sentences in a conversation, it is best to align representations of meaning to a single model.

While computer science allows a programmer to define any model, today’s knowledge graphs can be improved with tighter alignment to linguistics. It’s a simple application of cognitive science, but we need to chose what parts of cognitive science to adopt.

RRG distinguishes the meaningful world – semantics – with predicates that relate things and referents that are things. There are other components, but the building blocks of meaning can be accurately modelled as predicates and referents.

Knowledge Graphs

What are the differences between RRG and today’s knowledge graph?

First, there is a difference between the word forms in a language and their meaning. Second, a meaning can be described by many different word forms, depending on the situation. Third, some word form sequences can provide independent meaning to the composed words themselves. Lastly, knowledge graphs should align the predicate layers so comparisons can be made without using a program to perform the comparison. Comparisons should be automatic.

Semantic Predicates and Referents (not syntactic terms)

Rather than using words and syntactic descriptions to represent meaning in a meaning diagram (a knowledge graph) it is better to use semantic elements.

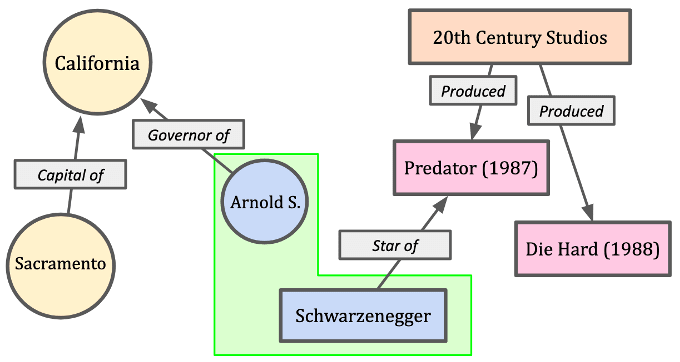

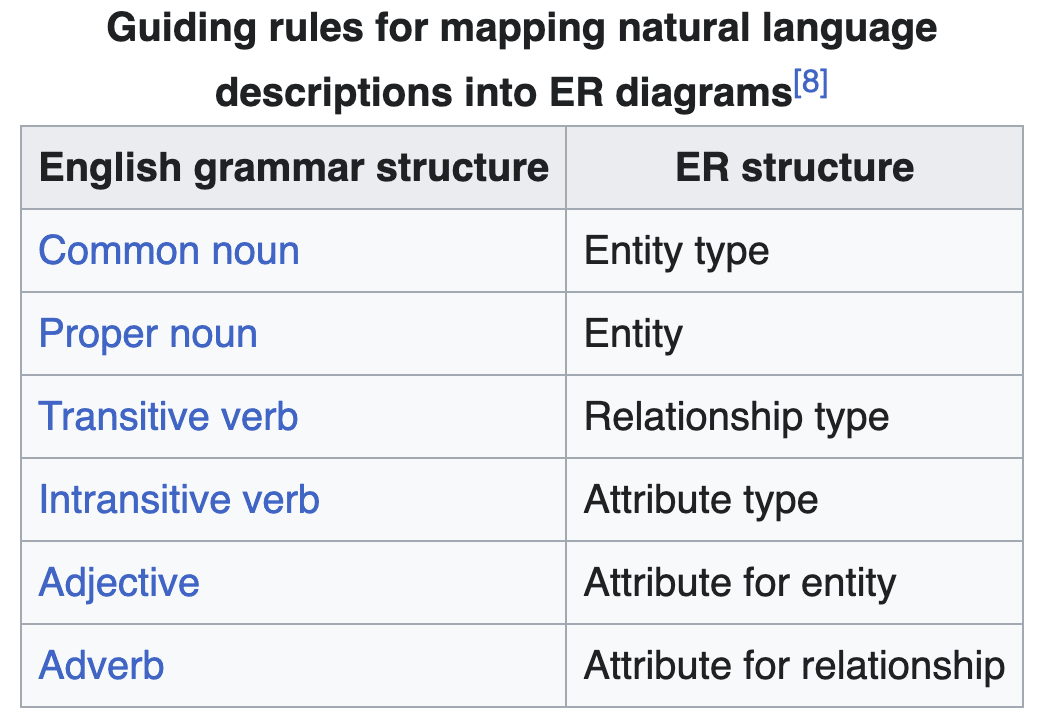

The following diagram (Figure 1) illustrates the limitations of meaning when represented by a particular language, like English. (Note, the figures below come from Wikipedia’s Entity-Relationship Model).

Figure 2 doesn’t generalize well because it relies on a human’s understanding of the words selected. Is “Governor Schwarzenegger” a valid name for Arnie? If so, it is left out! There are a number of possible ways to identify Arnie in English alone, which is why his referent should be uniquely identified by, say, r:arnie. This would link in English to the range of possible identifiers, directly or abstractly by phrase pattern (e.g. “Governor Schwarzenegger,” “Arnold Schwarzenegger,” “Arnold S. Schwarzenegger,” “Mr. Schwarzenegger,” “Mr Arnold Schwarzenegger,” “Governor Arnold Schwarzenegger,” “Ex-Governor Arnold Schwarzenegger,” and so on). r:arnie then represents all the language-specific terms that would identify it (including “the star of the movie ‘Predator’ from 1987”).

Is California the area laid out on the USA map? If so, the land doesn’t have a governor. Instead, a US state is a body that is governed by people and that body has a governor. Does land have cities like Sacramento? Isn’t that an area on a map? The point is that humans know a lot about the meaning of these labels (signs) that shouldn’t be excluded from the knowledge representation. Align knowledge with human capabilities — a process that starts with using meaning to represent knowledge, not English words.

In my language-based AI systems today, we use labels like r:sacramento to represent referents and p:produce to represent predicates. To make language independent, such dictionary word-senses would be better identified in a language-independent way, like r:123456 and p:654321. These semantic items would, of course, be best represented in a particular language with a mapping that identifies them in that language.

Of more importance is the nomenclature used in general in a knowledge graph. In Figure 3, the use of syntactic terms identifies entities and relations resulting in fundamental ambiguity of the model since relations of meaning (semantic predicates) can be both nouns and verbs (and adjectives and adverbs sometimes). Attributes such as time, space and reason (typically syntactic nouns, propositions and adverbs) are also predicates, but they are not clearly described.

In Figure 5, Predicates (Verbs) in RRG can have 0, 1, 2 or more arguments. This approach deals more naturally with the range of predicates like attributives, locations, temporals and more. We will use this to generalize far more easily and automate the comparisons of sentence meanings.

Nominals are important, too

A missing part of the Guiding Rules for ER above are nominalized forms of predicates. There are predicates that are syntactic nouns like derived forms (e.g. destruction) and action nominals (e.g. the destroying of…) and some that act like verbs but are used as nouns like infinitives (e.g. for the Vandals to destroy the city…) and gerund forms (e.g. the Vandals’ destroying the city was …).

*** End of Part 1 ***

*** In Part 2, the story continues to align knowledge graphs to align with the human semantic model identified in linguistics. How do we learn vocabulary? What kinds of phrases are there in RRG? How does the working parser convert efficiently from text to meaning and address the embedded meanings of sentences? Due out tomorrow. ***

Do you want to get more involved?

If you want to get involved with our upcoming project to enable a gamified language-learning system, the site to track progress is here (click). You can keep informed by adding your email to the contact list on that site.

Do you want to read more?

If you want to read about the application of brain science to the problems of AI, you can read my latest book, “How to Solve AI with Our Brain: The Final Frontier in Science” to explain the facets of brain science we can apply and why the best analogy today is the brain as a pattern-matcher. The book link is here on Amazon in the US (and elsewhere).

In the cover design below, you can see the human brain incorporating its senses, such as the eyes. The brain’s use is being applied to a human-like robot who is being improved with brain science towards full human emulation in looks and capability.